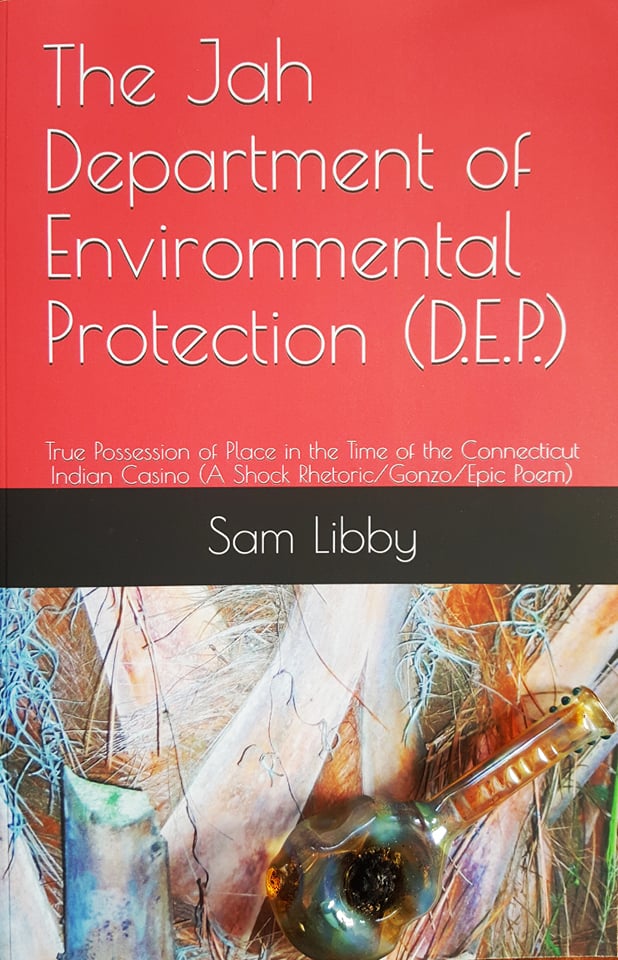

Sam Libby reading: THE JAH D.E.P CHAPTER 4 – THE SUMAC

“I submitted, yielded, obeyed to possess and be possessed, by place.” -Sam Libby This is, without a doubt, high art in the tradition of the English language’s greatest epic poems (read: Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘Aurora Leigh,’ John Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost,’ etc.) Like these authors imbued to their specific pasts and places, Sam has also created something specific to his borders of time and space, which is concurrently able to possess a sort of ineffable recognition of human nature’s cyclical course. A wheel of life. From Milton’s wondrous garden to Browning’s Italian vistas and wandering London streetscapes, we come to Sam – who will forever drink deeply of the water of his birthplace. So much is revealed – with equal parts compassion and malice – that the pervasively spiritual tone of Jah DEP becomes a duality in its own right. No strict heroes, no strict villains – even when the heroes and villains are very real. We live in a world constantly at odds with itself and its best intentions, which makes it all the more important to recognize our collective plight in this reality and stop the narrowing selfishness of human beings before it absolves us permanently from our privilege to live. I have had another sort of privilege just in getting to know Sam, and crossing paths with him many years ago. His poem’s influence on me now comes as no surprise given his influence on me then. Some of the best advice I’ve ever received, during a teenage existential crisis, came from Sam. Feeling trapped, and unable to relate on the same perceptual plane as others, I felt lost in my awareness of both self and others; and not knowing what to do with the abundance of information, I froze up. How would I move forward? Do I continue? How do we keep going, not knowing the origins of this crazily beautiful dream we all share? He reminded me, in his truly insightful way, that all I needed to do was participate. Be present and available to self and others. Do the thing. “Ya gotz to jump in der and dance da dance – wid dynamic uncertainty.” “Revel in joy because it’s joy?” I asked him. “…that makes sense.” His response was pragmatic, as always. “Sure beats da alternative…” I’m still going Sam, strong as ever and as present as ever. I too drink deeply of the water of my birthplace. -Luke Hunter

Writing spoils reading for the writer. A preoccupation with style and narrative voice makes any text which lacks snap seem insipid, execrable, 97% of all books are insufferable. It was therefore pleasant to find that Sam Libby’s “The Jah DEP,” is in that three percent of books. I couldn’t put it down – it kept me up past my bedtime. A thunderstorm of gonzo journalism with sentences and fragments like lighting bolts, “The Jah DEP” hovers over the reader’s head for a time. Its light changes the land.

The reader had better accept the book’s terminology, ideas and assumptions; there is no escaping them. The insistence of the narrator, while occassionally maddening or seeming mad itself, gives the book its stormy power. The story is a tale of betrayal in natural surroundings. Libby lived in a house built of a fallen tree on the North American Wildlife Association’s (NAWA) wildlife refuge in East Lyme, CT. He is Robert Salvatore’s (a founder of NAWA) apprentice in the growing of cannabis and its neo-shamanistic use. But the refuge is “the kingdom of Robert’s herb, founded on resentment.” It is the cult of the pathetic wild animal,” where people fuss over dying raccoons but are callous and cruel to each other. As the story of the refuge and its bust unfolds, the animal lovers seem more and more unsavory. There is a memorable Judas figure.

The chapters are headed mainly with quotes from D.H. Lawrence’s “Studies in Classic American Literature,” one of my favorite authors, and a work I haven’t read. Lawrences book concerns true psychic possession of place, and how white people in America have never achieved it. Libby brings Lawrence’s ideas to the present Southeast New England of the Indian casinos.

He argues that the Indian casinos are in no way Indian entities since they exclude the vast majority of people with the tribal blood. Libby says the Indian casinos are nothing but manifestations of corporate greed, a betrayal and denial of the sanctity of the place and the ancestral spirit.

Uncas of the Mohegans and Skip Hayward of the Mashantucket Pequots are targets. But annexation and casino foes beware. Libby hates the white establishment, much more.

Libby sees resentment as a primary motivating force in the human condition. The universality of the resentment makes all of us “niggahs.” This idea takes getting used to. The word is offensive despite the hip hop spelling, and use. “We are all niggahs,” the book declares, which made me laugh, for I’ve never felt that way. Yet the theory of resentment is a sadly apt one. It helps explain Connecticut colonial history and how that history has evolved into the present situation.

This is the sort of book of maddening intensity that provokes intense polarization either for or against. After reading the book it is hard to support current marijuana laws. For Libby, the natural right to use all plants is a matter of pressing Constitutional and spiritual importance.

Though told by this ancient mariner of a narrator, who grabs you by the collar and won’t let you go, the story is scant on autobiography. We have little idea how Libby came to the crisis depicted here. There are tantalizing glimpses of his youth in Norwich and a moving testimony to his father, a famous political “gadfly.” I hope Libby’s next book will be even more personal.

Journalist/author Sam Libby returns to the land of his birth at a critical juncture in his own life and in the life of his small southern New England hometown as it becomes transformed by the towering glass and steel presence of Connecticut’s massive multi-million dollar casino industry. Here, Libby, through his first-person interactions with members of the area’s aboriginal Indian tribes, gives us a rare inside look of a proud, defiant people (RIP Moonface Bear) struggling to maintain their sense of place, their ownership of their indigenous land, their spiritual ties to their elders as the bulldozers rape the lush New England forests and thousands upon thousands of casino dollars seem to rain from the sky.

Through a parallel narrative, Libby also tells the story of his own journey, his never ending quest for greater understanding of the real spiritual truths, a journey marked by resistance to the selfish capitalist system destroying our lives and our earth, a journey of embracing the true aboriginal tribal spirit, of respecting nature and all its beauty and strength. Here, Libby is at his best. In intense, sometimes poetic, sometimes near ranting, Gonzo journalism style, Libby urges us to join the revolution, to “rise up out of the box” and fight back against “the man” and all of the evils He has brought to the world, to drain “The Great White Swamp” and take righteous ownership of our natural sense of place.

Choosing to live in a self-made refuge deep in the woods of the North American Wildlife Association, Libby doesn’t hide his affection for cultivating and using the finest “herb” – an affection that becomes an integral part of his journey and story and message. He embraces the beautiful nature around him, the wild animals and all of the symbolism he perceives in his almost shamanistic attunement with his surroundings. Nowhere is this more evident than in the captivating tale of the iconic Split Tree. There is also a sense of tragedy and betrayal as Libby learns the hard way that those he thought shared his devotion to nature and the indigenous tribal spirit were in fact like everyone else chasing the mighty dollar. He suffers great consequences as a result.

In the end, this talented author sews the two narratives together – the Indians, the Casinos, his own spiritual journey, his fierce refusal to become just another “car key carrying chimpanzee” – to share – and sometimes shout – to us the message that the we must all rise up, claim what is ours, protect what is ours, find our place in the beautiful world around us and protect it from the always encroaching selfish, capitalistic threats upon us. At a time when our world is quaking with protests about climate change, protests about economic injustice, protests about political and social injustice, Libby’s message of resistance and nurturing and protecting what truly matters is as timeless today as it was in Connecticut in 2003 when JAH was first published. For it is not the state or federally-sanctioned Departments of Environmental Protection that preside over our natural earth but it is the Jah – to many the Rastafarian God – D.E.P. that we must ultimately respect and nourish.

Colin Poitras – Pulitzer Winning Journalist