Sam Libby for the New York Times

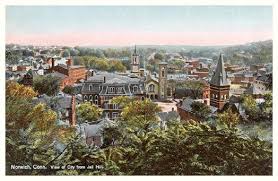

CITIES with imperial pretensions often claim to have been built, like Rome, on seven hills. Norwich is one of those cities. In 1865 it had more millionaires per capita than any other city in the United States, said Dale Plummer, the city historian. Many of the tallest hills are named for the families that built the most prominent homes on those hills. But the seventh hill, the hill with the most sweeping views of the harbor at the confluence of the Shetucket, the Yantic and the Thames rivers, the hill that should have been the city’s acropolis, is still known as Jail Hill, although the county jail was demolished in the 1950’s.

Jail Hill’s unusual community and history was recognized last month when the State Historic Commission listed the neighborhood encompassing Fountain, Happy, John and Old Fountain streets as well as sections of School and Cedar streets on the National Register of Historic Places.

The designation marks the recognition of the Jail Hill community as one of the most significant black neighborhoods in the United States from the 1830’s to 1860’s, Mr. Plummer said. ”The black community of Jail Hill,” Mr. Plummer, ”consisted of a number of individuals of importance in the struggle for abolition of slavery and educational opportunities for people of color.”

In pre-Colonial and early Colonial times, the summit of the hill, which rises 223 feet from the harbor, was a strategic fort in the Mohegan Tribe’s conflict with the Narragansett. The summit has commanding views including these days the towers of the Foxwoods Casino and Resort.

The hill was home to the dispossessed, people of color who were a vibrant counterculture to the white, Congregational Church-dominated mainstream culture, Mr. Plummer said. Lester Skeesucks and Sally Prentiss, both members of the Mohegan Tribe, married into the city’s black community and were important members of the Jail Hill community.

Since early Colonial times much of Norwich’s commerce was with the West Indies. At an early point in the city’s history there were many slave owners in Norwich. A large free black population existed by the time of the American Revolution, Mr. Plummer wrote in the report he submitted to the State Historical Commission.

Anti-slavery sermons were delivered from the pulpits of the city’s churches as early as 1774. But because of the commercial connections between Norwich textile factory owners and Southern cotton plantation owners, and the fears of the white working class that blacks would imperil their jobs and reduce wages, there was a large pro-slavery faction in the city also, Mr. Plummer wrote in his report.

”One of the early anti-slavery meetings held in the Presbyterian Church was broken up by a mob — the pastor escorted to the town line and threatened with a dose of tar and feather if he dared return,” wrote John E. Rogers, director of the Afro-American History Department at the University of Hartford, in the introduction of ”The Autobiography of James L. Smith,” which was first published in 1881 and later reprinted in 1976. Mr. Smith was a slave who had escaped from Virginia and settled in Norwich, building a house at 59 School Street on Jail Hill. He was a shoemaker and a Methodist minister who wrote of the hardships and cruelties of slavery as well as the kindness — and the discrimination — he found in the North.

Before the county jail was built on the summit of the hill in 1828, it was known as Kinny Hill, because it was owned by the Kinny family, who had built a home on the hill’s lower western slope, Mr. Plummer discovered in his research.

In the 1830’s and 1840’s many people of color built on the hill because the prison lowered property values.

”There are indications that the Kinnys were abolitionists who purposefully sold the land at fair market value to people of color,” Mr. Plummer said.

Mr. Plummer also said, ”There seems to have been a strong sense of community in the Jail Hill neighborhood.”

The community included David Ruggles, who was born on Jail Hill and served as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. He is credited with helping at least 600 slaves escape to freedom and worked closely with the abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass, also an escaped slave.

Steamboats from New York and other southern ports would go to Norwich, which was the southern terminus of the Norwich and Worcester Railroad and an important station on the Underground Railroad, a network of people and places that helped slaves in their flight. (It was the route taken by Douglass in his escape.)

At least 60 men of color from Jail Hill served as ”substitutes” during the Civil War. Substitutes would be paid $350 and take the place of affluent draftees. Dennis T. Walker, an escaped slave, became the servant of Col. Griffin Alexander Steadman, early in the war. He fought with Colonel Steadman until he was killed at Petersburg in 1864. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, men from Jail Hill served in the 11th Connecticut Volunteers, one of the first all-black regiments.

Members of the Harris family were active abolitionists living on the hill. They were agents and distributors of the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, published by William Lloyd Garrison. Members of the Harris family attended the Prudence Crandall school for girls and women of color in Canterbury. The family was embroiled in the controversy of whether black children should be educated, Mr. Plummer said.

James Spelman, who was born on Jail Hill in 1841, became a prominent journalist for black and mainstream publications.

John Fox Slater, a white industrialist who was heir to the Slater textile mill fortune, was not born on the hill, but a resident of Norwich who had a profound influence on educational opportunities for black people. Perhaps at the urging of ministers of the Second Congregation Church (which was on the lower southern slope of the hill and provided the first educational opportunities for black children in Norwich) donated $1 million to establish schools nationwide for black children after the Civil War.

Following the Civil War, Irish, Eastern European and Jewish immigrants made the hill their home and gateway into the American dream. But through the 20th century the neighborhood decayed and today the neighborhood contains many derelict buildings.

”The recognition of not only the black history of the hill but also the history of all the other ethnic groups who were considered outcast could be an important element in revitalizing Jail Hill,” said Robert Kinny, who is not a descendant of the original Kinny family of Jail Hill, but a property owner and current resident of the hill.

The first thing to do to restore a derelict property is to restore the stone and cement walls that terrace the hill, said Jonathan Edward Sirois Sr., who is restoring a property on School Street. ”When you restore one of these properties you can appreciate the hard work and determination that allowed people to make their home on the side of a high, steep and rocky hill,” he said.